One day when my sister and I were really quite young and our maternal grandmother was on a visit she had us painting large flowers and leaves at the table in what our parents called the breakfast room. When they were dry we cut them out, and using a long horizontal pencil line as a guide, stuck them up close together along one of the walls. I don’t remember how high on the wall they were but to my child’s eye view it was as if I was laying in the long grass looking at daisies and other assorted wild things.

Later I came to realise that most of the paintings on the

walls of my grandmother’s, my aunt’s and my childhood homes were her work.

Later still I worked out that there was a store of other paintings the

grown-ups thought didn’t merit a place on the wall. They knew her as an amateur

painter and found her work decorative. To me there was a magic to be found in

many of them, but it soon became obvious that what I saw was not what the others

saw.

Slowly over the years I’ve inherited the paintings of hers

that I value the most, with the exception of one which still hangs in my

father’s house. Part of the value I ascribe to my grandmother’s work has its

source in having witnessed at a young age the magic of her creating the

illusion in the first place. But I was also around to see her stop painting in

the last years of her life. She went, as so many did, from living

independently, to being in a nursing home, to spending the final year of her

life on a ward for the elderly mentally ill in one of the local psychiatric

hospitals. I didn’t visit her after she left her last home, I was about

fourteen at the time and my mother said I didn’t have to visit if I didn’t want

to. I said I’d rather not and that was accepted by the family. But the truth is

somewhat different. I didn’t visit anymore because my Grandmother had told me

not to. It had been my habit to go to her flat once a week after school. I

witnessed her mental decline, the increasing inability to take on new memories.

She knew what was happening to her and she knew she appeared different to me. I

won’t repeat the actual conversation, sufficient to say I interpreted her to

mean; ‘I don’t want you to see me like this’. She, increasingly unable to make

memories, wanted my memories of her to remain intact.

So in time my mother and my aunt became the custodians of

one half of my family history. Along with my grandmother’s paintings came a

mass of photographs and documents. Later my Great uncle died (brother of my

Grandmother’s husband) and the rest of that side of the family’s history became

available to view. In this computer age, which has given such an impetus to the

idea of a family history, it slowly dawned on me that one of my ancestors above

all had given this side of the family a history.

Hebert Crosoer (1859-1934), was a tailor from Ashford in

Kent, his hobbies were photography and family history. He traced the family

tree of our ancestors (Huguenots) back to the seventeenth century, almost to

the point where they stepped of the boat from France. And he took pictures of

the gravestones whenever he got the opportunity, lugging his heavy camera and

tripod around the country. I once stumbled upon a reference to a particular location,

but for me it was only a matter of minutes, courtesy of Google Earth, before I

was looking into that churchyard. He left eighteen photo albums, the one of his

honeymoon on the Isle of Wight was given to me by my mother many years ago.

Just browsing the pictures and the short captions with the benefit of a little

knowledge about early photography turned out to be a revelation and seemed to contradict

a family myth.

Herbert married Ellen Mary Giles (1866-1951), she was

remembered by my mother and aunt as a strict Victorian grandmother with a moral

code to match, who invaded their childhood home during her final years. She was

also credited with dressing her younger son (my Great uncle) in female baby

clothes (because she really wanted a girl), which was recalled as being in some

way related to his lifelong speech impediment (a profound stutter). But the

honeymoon album tantalisingly suggests a different character, at least in youth.

Many of the photos are really self-portraits, though you wouldn’t know it

without knowledge of photography in the 1880’s. They were not a wealthy couple,

but the album they put together would have impressed everyone they showed it

to. The pictures are of a couple, appropriately in love, relaxed and lounging amongst

scenic locations from across the island. They were all made within a week of

the marriage ceremony. Together they must have organised the pony and trap, the

heavy tripod, the large camera, the box of ‘half plate’ glass negatives, found

the locations and the weather, composed themselves in an intimate but

respectable way, hidden the shutter release (held in Herbert’s right hand) and

of course ‘held the pose’ for up to half a second in order to get the correct

exposure. This couple acted as one, it couldn’t have been organised in the time

available unless they had. Neither could have dictated to the other. This

couple knew each other very well before they were married.

There are other pictures of their first home, of his

chair and her chaise lounge. We have all inherited a cultural belief in a repressed

Victorian sexuality, I wonder? In practical terms engagement meant being given public

permission to be alone together. She, according to popular fiction, retires to

the withdrawing room with the ‘vapours’, he goes down on one knee, half an hour

later they emerge engaged to be married… Now, when just about any of us can call

ourselves a historian, the problems of historiography multiply. Any follower of

the television series Who Do You Think You Are will know that there always

comes a point when the celebrity family historian starts to empathise with a

particular ancestor and states how, not just genetically, but psychologically

some part of that distant relative seems to live within them today. This is

dangerous ground indeed. As for Herbert, I’ll leave further elaboration of that

story until I’m in a position to show you the evidence.

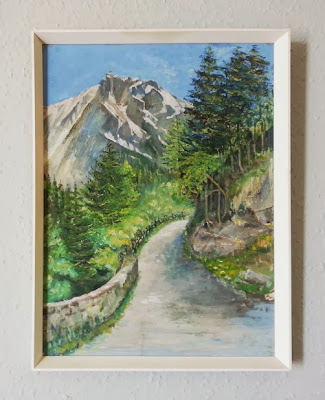

Since the death of my mother and my aunt I’ve had access

to more information about my artist Grandmother. One example is knowledge of

the context in which the above picture was painted, it’s a favourite and has

hung on my wall for more than twenty years. But part of the reason I was allowed

to take possession of it the first place was that it wasn’t a particular favourite

of any of the rest of the family. The composition is classic and simple,

perhaps banal to the more sophisticated. But the location is real. It was

painted on a trip to Switzerland which she undertook with her local art group

in the early 1960’s. That much I always knew. But it wasn’t until I was

sorting through my late aunt’s possessions that I found the following.

In the future we will know more of the past. This is true

of both recent and more ancient times. One of the awareness’s of age is not

just that ‘everything our parents/teachers/other authority figures taught us was

wrong’, but that new technology makes available masses of additional evidence or

data to argue over! Equally, it appears that for the foreseeable future computers will not have a

problem with memory capacity, and so should we choose to, then what we post on

the Web can not only be available to anyone, but for an indefinite period in

the future. It is a slightly scary thought. I often pause to check in my own

mind whether I'm really happy for anyone to know what I’d like to say. But one

should also be aware that the same patterns of self-censorship are being

applied by the viewer of Web content as they are in any other realm of life. So

what is useful to share of a family history, perhaps those aspects

which are not common to all families?

It is remarkable how much

of the 20th century was recorded on film, and is rapidly becoming available in

bite-sized chunks on YouTube and elsewhere. At some point one of our family

will almost certainly place on the Web the forty minutes of black and white, nine

and a half millimetre cine film, taken by my maternal Grandfather in the 1930’s

and 40’s which features, albeit fleetingly, all the characters mentioned above.

I’ve yet to find on the Web the aerial movie film shot by Claude Friese-Greene

from a biplane in 1919 and restored by the British Film Institute, showing the

down Cornish Riviera Express leaving Exeter, travelling down the Exe estuary,

onto the sea wall and passed my window. Perhaps I should post it myself.

Written records, slowly

becoming digitised and available in an easily searchable form, abound for the

last few centuries. It is a highly skewed record of course, produced by and

reflecting the concerns and priorities of mostly educated, relatively wealthy

and powerful men. What is less well known is that museums, local records

offices, government departments, the National Archive and numerous other

organisations have massive warehoused collections of which they themselves are only

vaguely aware of the contents. For many ancestor hunters however the story does

appear to dry-up in the eighteenth or seventeenth centuries unless someone was

particularly well connected. If your family were in any way connected to the

English court, then you may find much to amuse in the Tudor period. It tends to

be the most popular period in English history, not least amongst television

producers. The reason for this is simple; it was the first time that detailed

records of day to day activities were maintained. Modern-day bureaucracy was

born at that time, and many a modern academic career has been built on the back of

long hours spent bent over Henry VIII’s laundry lists! Another possibility is that

you have an ancestor who belonged to a minority religious group for whom

membership of, and identity with, the group was their particularly priority in

life. The story of the founding of a New England, and therefore an America,

became the dominant narrative because the Puritans recorded everybody and everything

which went aboard the Mayflower. Puritan identity was reinforced by their

invention of additional Christian names like Verity, Prudence etc.

But it may be that in the

future a personalised family history need not shade away to something remote in

time and place, alluded to only in less accessible history books. We can increasingly access

thousands of years of family history. Facebook is not just the biggest social

media network of now, or for the future - it is also a resource for the past. Hewling

and Crosoer are two of the less common surnames, search them on Facebook and

you have an instant ‘data set’ of manageable size, just let your eyes scan the

faces. We were vaguely aware that a Hewling had once migrated to the West

Indies, there are plenty of black Americans with the name Hewling on Facebook.

Genes get passed on complete or not at all, they are digital and don’t get mixed

like items from a recipe which is then cooked. So there are distinct facial

characteristics, you may have the nose of one grandparent, the forehead or chin

of another.

DNA only tells you about

the past, genetics is the study of the past. Anything else is about uncertainty

- forecast, prediction, probability. DNA profiling will become commonplace and

what is tells you about your ancestry can be accepted with much greater

confidence than what it says about the probability of you suffering a fatal disease

thirty years in the future! It is a relatively simple comparison with a data

base of over two hundred thousand samples, gifted by people from every location

on the planet, who have had close family living in the same place for at least

three generations. For example, it can tell you how much of you is northern European,

how much of you is from elsewhere; and that, combined with other data, can tell

you how long your ancestors have been here and their migration route since all

of us of non-African descent shared a common female ancestor who sailed out-of-Africa eighty thousand years ago. It may tell you that you carry the genes of

humans other than homo sapiens.

The story of genetics is

the same story as the creation of different languages and the story of human migration.

When I was a child I asked my mother if she was born in the Middle Ages,

after-all she'd described herself as middle-aged! Now I can state with some

confidence that we, with all the same physical and mental capacities and

capabilities have been around for between one hundred and eighty and two hundred

thousand years. We live in one world in so far as we are prepared to think in

an evolutionary way. But I can also 'see' our ancestors; the view from my

window as I write is of Lyme Bay (well Berry Head to Portland - on a good day!)

Whilst their human remains lie in the sands below the English Channel, in my

imagination I can visualise the lower sea levels of earlier times (at the last

glacial maximum sea levels were one hundred and twenty metres lower than today),

the channel as one vast river plain and estuary fed by the Rhine, the Thames

and the Seine and at times easy enough to cross.

No comments:

Post a Comment